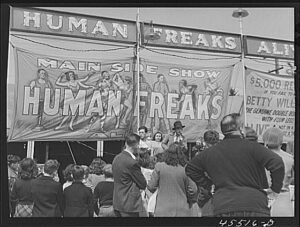

Through her work, Extraordinary Bodies, Rosemarie Garland Thomson explores the success of the 19th century American freak show. During this time, America was in a period of transition. In the relatively new country individuals were struggling to define their status in a society that claimed to stand against any categorization of individuals into a social hierarchy. The undefined nature of social status within a democracy created an anxiety among citizens. The author attributes a large proportion of the American freak show’s success to its ability to assure the masses that they were normal in comparison to those on display. Through this soothing of anxieties, the American freak show illustrates that the social hierarchy within a democracy only differs from that of an aristocracy by the motives behind the categorization of individuals.

Democracy is often defined by the core value of equality, however, throughout her work, Thomson exposes the limitations of equality within a democracy. On the surface, equality appears to be synonymous with freedom and the celebration of individual’s unique attributes. However, according to Thomson, equality actually encourages a leveling of citizens and in turn causes individual variations to be seen as deviances and threats. This phenomenon caused America’s great experiment in democracy to bring about the “cultural dilemma regarding the extent to which individual  variations could be tolerated.” (64) The limitations of equality within a democracy are illustrated by the success of the American freak show. The individuals displayed in the freak shows were physically nonconformist to the established American norm or ideal and therefore represented the latent threat that differences may result in anarchy. The freak’s physical abnormalities “invoked the tensions between uniqueness and uniformity” (66) that illustrated democracy’s promotion of equality, or rather mass culture, instead of freedom for the individual.

variations could be tolerated.” (64) The limitations of equality within a democracy are illustrated by the success of the American freak show. The individuals displayed in the freak shows were physically nonconformist to the established American norm or ideal and therefore represented the latent threat that differences may result in anarchy. The freak’s physical abnormalities “invoked the tensions between uniqueness and uniformity” (66) that illustrated democracy’s promotion of equality, or rather mass culture, instead of freedom for the individual.

Democracy as an ideology placed the average man in a position of power previously held solely by kings and aristocrats, and in turn positioned the American ideal at the top of the social hierarchy. This political change created social anxiety. Instead of knowing one’s relative place in society due to strict social classes and a defined model – the aristocratic king – one looked up to the “normate position of masculine, white, non-disabled, sexually unambiguous, and middle class” (64) individual. Due to historical changes, those who identified with this superlative were now competing with immigrants, people of color, and women for jobs and benefits that were previously given to them based upon physical appearance alone. The ability to identify with the ideal no longer had the protection and security it maintained in an aristocratic society.

On the surface, America was blatantly against any form of social hierarchy, for this reason “identifying and claiming status is perhaps the greatest anxiety in a theoretically egalitarian and volatile modern order, the boundaries of power must be clear” (64). Those with extraordinary bodies acted as the boundary Thomson identifies within this quote. Those on displayed were presented as the opposite of the American ideal, and in comparison onlookers viewed themselves as closer to the ideal they were striving for. This phenomenon created a sense of social structure that reassured the masses they were normal, or at the very least socially superior to the freaks on display. The wide physical disparity created by the categorization of the freaks created a social hierarchy that eased onlookers’ fears and anxieties.

Democracy is often defined by the core value of equality, however, throughout her work, Thomson exposes the limitations of equality within a democracy. On the surface, equality appears to be synonymous with freedom and the celebration of individual’s unique attributes. However, according to Thomson, equality actually encourages a leveling of citizens and in turn causes individual variations to be seen as deviances and threats.

Proprietors of freak shows gave the people on display various aristocratic titles such as “’King,’ ‘Queen,’ or ‘Princess’” (67) in order to further distinguish the contrast between the so called freaks and the American ideal. These individuals were further alienated due to their association with clearly British titles which tied them to a culture many Americans felt a great animosity for. Aristocracy promotes the individual and clearly places one, typically a king, at the top of the social hierarchy. Therefore, ritual and decoration is meant to make individuals feel elite and closer to the aristocratic individual. However, the ritual and decoration that was prevalent in the American freak shows acted to further the othering of those with extraordinary bodies. The stark contrast between freaks with aristocratic stage names and the America ideal recreated the “fixed social hierarchy that America imagined resisting” (67). Here, Thomson implies that the social hierarchy within a democracy may not be that different from that of an aristocracy.

The America freak show reproduced aristocracy within a democracy. The individuals on display at the shows calmed the onlookers’ unease by allowing them to feel closer to the norm or ideal.  However, the othering of these individuals created the very fixed social classes that America vocally resented. Instead of celebrating these individual’s unique physical characteristics as the pillars of freedom and individualism would allude to, the so called freaks were ostracized and categorized. This phenomenon illustrates that aristocracy and democracy’s social structures are not as different as they appear on the surface. The difference lies in the intent, not the structure of the ideologies as both categorized individuals but for different purposes. Aristocracies utilize ritual, decoration, and titles to distinguish the elite as better than the masses. In contrast, the America freak show illustrates the same techniques to distinguish the unique from the masses and allow onlookers to feel closer to a generic ideal. This phenomenon demonstrates that the American freak show was a way of reproducing the very fixed social classes they outwardly protested.

However, the othering of these individuals created the very fixed social classes that America vocally resented. Instead of celebrating these individual’s unique physical characteristics as the pillars of freedom and individualism would allude to, the so called freaks were ostracized and categorized. This phenomenon illustrates that aristocracy and democracy’s social structures are not as different as they appear on the surface. The difference lies in the intent, not the structure of the ideologies as both categorized individuals but for different purposes. Aristocracies utilize ritual, decoration, and titles to distinguish the elite as better than the masses. In contrast, the America freak show illustrates the same techniques to distinguish the unique from the masses and allow onlookers to feel closer to a generic ideal. This phenomenon demonstrates that the American freak show was a way of reproducing the very fixed social classes they outwardly protested.

The importance of the reproduction of aristocratic social hierarchy within democracy as illustrated by the 19th century American freak show is still relevant today. The American ideal remains a prevalent concept in today’s society and is continuously tied to the image of a white, middle class, physically able family. While those who do not fit this definition are no longer put on display and ostracized, they are often looked upon with pity, as if they are lacking something. The physically disabled is a prime example of phenomenon. Instead of embracing physical abnormalities, modern society looks at them as something to be fixed. While this categorization is not as extreme, it still implies that the physically able are superior to the disabled. This creates a social hierarchy in modern day society that is reminiscent of an aristocracy.

Through the analysis of the success of the 19th century freak show, Thomson implies that the social structure of a democracy may not be that different from the aristocratic social hierarchy it condemns. Thomson explicitly says that democracy is not as egalitarian as presented on the surface. The American freak show exemplifies democracy’s limitations in accepting individual variations despite the ideology’s outward portrayal. In fact, in pursuit of equality, the ideology has destroyed individual freedom and replaced it with mass culture. Individuals within the society now strive to identify with the American ideal. The freak shows acted as a way of calming onlookers’ anxiety, reminding them that they were not that far from this superlative, that they were normal. In fact, Thomson alludes that through the othering and categorization of those with disabilities, democracy created a new type of aristocracy embedded into the country’s social hierarchy.

Bibliography

Thomson, Rosemarie Garland. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. New York: Colombia University Press, 1996. Print.