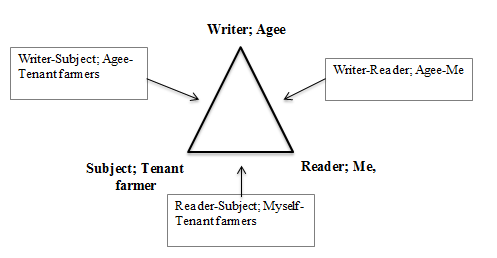

In documentary writing, three relationships are at play: those of writer to subject, reader to subject, and writer to reader. With respect to James Agee’s and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, these relationships are configured as those between Agee to the tenant farmer families, the reader to the tenant farmer families, and Agee to the reader. Because Famous Men documents the lives of marginalized and impoverished persons in the 1930s rural South, the relationship between the tenant farmer families and the historical reader is most pragmatic and potentially vital in regard to political change. ((The notion that the reader-subject relationship is vital is based on the readers of the book as the ones who ultimately have the power to affect change in the lives of subjects. Neither the relationship between Agee and the families nor the (mediated) relationship between Agee and a contemporary reader will have any bearing on change in positive change in the lives of the tenant farmer families.)) Yet, each of the relationships that obtain among reader, writer, and subject are significant since readers’ reception (including mine) depend upon their totalizing interaction. One of the most interesting techniques in Agee’s rhetorical repertoire is the explicit commentary on his difficulties and challenges as a documentarian. Some find that these recognitions enhance Agee’s reputation; others, however, see this commentary excessive and self-indulgent. Do these moments improve the writer-reader relationship, thereby strengthening the reader-subject relationship, or do they weaken the writer-reader relationship, thereby diminishing the reader-subject relationship and, ultimately, the political efficacy of Agee’s work as a whole?

I do not find the answers to these questions obvious. Revealing difficulties is a double-edged sword, and Agee walks a fine line between self-interest and honesty in his use of metadiscourse. On the one hand, by making readers aware of the difficulties and indeterminacies of documentary work, Agee builds both his ethos (ethos refers to the writer’s attempts to develop his credibility in the minds of readers) and the reader’s respect for the difficulty of his task. ((I characterize this difficulty as a near-impossibility given the constraints of time among the tenant farmers, the constraints of writing as a medium, and Agee’s status as an outsider.)) On the other hand, Agee may be thought to undermine his readers’ confidence in his writerly expertise and engage in excessive modesty by making his struggles known to readers. ((This modesty is excessive because it seems incongruous with moments when Agee uses an experimental writing style that signals extravagance rather than modesty.)) Ultimately, because of their positive effect on the writer-reader relationship, I will argue that references to Agee’s failures, difficulties, and challenges as a writer enhance the effectiveness of the documentary as a whole.

Let us consider a first claim: Agee strengthens his ethos by demonstrating his fallibility as a writer. The following passage represents what some find to be Agee’s honest (even courageous) acknowledgment of his limits and failings:

If I could do it, I’d do no writing here at all. It would be photographs; the rest would be fragments of cloth, bits of cotton, lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces of wood and iron, phials of odors, plates of food and excrement. . .A piece of the body torn out by the roots might be more to the point. As it is though, I’ll do what little I can in writing. Only it will be very little. I’m not capable of it; and if I were, you would not go near it at all. For if you did, you would hardly bear to live. As a matter of fact, nothing I write could make any difference whatever. ((Agee, James and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001), 8.))

Notice Agee’s repeated use of the pronoun “I” coupled with the strong assertions about the limits of his authority as a writer that he levels at himself. Agee’s use of the personal pronoun shows that he is fully accountable for the ways in which his representations of the tenant farmer families fall short. Instead of making excuses for his work, Agee takes responsibility. In addition, his short sentence structure and simple diction direct any blame for fault in the work directly back to himself, as a writer.

Ultimately, because of their positive effect on the writer-reader relationship, I will argue that references to Agee’s failures, difficulties, and challenges as a writer enhance the effectiveness of the documentary as a whole.

These reasons involve at least one complication that may impinge on the claim. The construction of Agee’s ethos is characterized by a sense of modesty. After he has made such an effort to explicitly state his limits as a writer, we, as readers, expect his writing to be correspondingly modest in style. However, Famous Men is nearly everywhere marked by an unconventional experimentation with style, techniques such as page-long parentheticals, including parts of words from a “scissored hexagon of newsprint,” and unusual punctuation such as “( (?) ) :)” that are anything but modest. ((Ibid., 72.)) I will grant that Agee, as a novelist by trade, might see these techniques as honorific to the tenant farmers because of their artistic complexity. However, readers might well be troubled by such style because it calls more attention to the aesthetics of language than it does the subject itself. ((Agee, after all, charged with representing human subjects who may be harmed by being depicted by experimental means.)) Agee’s experimental  style, typically reserved for fiction, seems incongruous with his seeming modesty exhibited in the passage above. Accordingly, readers may question the sincerity of Agee’s modesty. How can it be genuine when he risks such subjective portrayal? While on the whole I find Agee’s acknowledgment of limits beneficial, Agee never explicitly calls attention to his experimental writing techniques, which seem beyond scrutiny. If anything, highly stylized passages exhibit a measure of writerly skill and power, a kind of extravagance at odds with modest limitation.

style, typically reserved for fiction, seems incongruous with his seeming modesty exhibited in the passage above. Accordingly, readers may question the sincerity of Agee’s modesty. How can it be genuine when he risks such subjective portrayal? While on the whole I find Agee’s acknowledgment of limits beneficial, Agee never explicitly calls attention to his experimental writing techniques, which seem beyond scrutiny. If anything, highly stylized passages exhibit a measure of writerly skill and power, a kind of extravagance at odds with modest limitation.

Let us consider a second claim: Because Agee acknowledges the documentarian’s difficulties, the reader builds respect for the near impossibility of his task.

These notes, which might well be the proper device for any amount of expansion, redefinition and linkage, must be just as brief as I can make them. It will probably be necessary to make unsupported statements, and to raise problems rather than to try to answer them. Of the unsupported statements, please know that I have considered their backgrounds as scrupulously as I am able; and of the problems, that I want to “answer” or at least consider them as fully as possible in the course of time. [Emphasis mine.] ((Ibid., 177.))

The phrases “to raise problems rather than to try to answer them” and “as scrupulously as I am able” are examples of Agee not only calling attention to his own fallibility, like the first argument, but also explicitly referencing the lack of any definite conclusions to be drawn from the book. Presumably, Agee would have a much better chance than any reader at understanding the tenant families due to his time spent with them, but he is careful to avoid oversimplifying the complicated issue of representation and misrepresentation of the subjects. Because he makes known the improbability of his task as a writer, he gains respect from readers who become aware of his position. The  quotation marks around the word answer exemplify another moment when Agee is showing readers that he, much less they, cannot be an expert on tenant families after spending time among them or reading Famous Men. Though I focused on Agee’s use of the first person in my earlier example, we might also consider how Agee suggests the constraints of writing as a representational medium when he says, “nothing I write could make any difference whatever.” By doing so, he has again shown how tough the task of documentary writing is, and thus catalyze his readers’ respect for his work.

quotation marks around the word answer exemplify another moment when Agee is showing readers that he, much less they, cannot be an expert on tenant families after spending time among them or reading Famous Men. Though I focused on Agee’s use of the first person in my earlier example, we might also consider how Agee suggests the constraints of writing as a representational medium when he says, “nothing I write could make any difference whatever.” By doing so, he has again shown how tough the task of documentary writing is, and thus catalyze his readers’ respect for his work.

On the other hand, one could argue that Agee’s pointing out the difficulty of his task may weaken his authority and diminish his ethos. If we typically expect writers to possess a measure of intellectual authority, it is disconcerting to hear Agee question his expertise. Yes, perhaps we are always subconsciously aware that authors are fallible, but we also trust that they have a high degree of skill. If the writer, who guides whatever understanding of the subject we may glean, questions his descriptive powers, then our relationship to the subjects–the most important relationship in the ultimate effort to sponsor change–is weakened.

If we typically expect writers to possess a measure of intellectual authority, it is disconcerting to hear Agee question his expertise.

Clearly, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is not a book for all readers. It is not a documentary that offers quick answers, definitive solutions, a settled case, or conclusions without questions. It is a work that is best for those who value the writer’s admission of fallibility and recognition of error as characteristics that enhance author rather than diminish expertise. Readers can be receptive to Agee’s acknowledgement of difficulty, adopting the epistemological position that the robust recognition of limits enhances readers’ perception of honesty, trustworthiness, and accountability. Readers of this type realize that, like Agee, they are engaged in a quest for knowledge that is, by nature, marked by partiality. Such readers understand that rhetorical constraints are both inevitable and deserve to be valued.

Bibliography

Agee, James and Walker Evans. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001).